Some iteration of this piece previously appeared in Elle magazine.

You threw a lemon at me and hit me in the forehead

That’s what love does to you/makes you cheeky

Ay, I love you so much that I just can’t punish you

- A bulerias from Carlos Saura’s “Flamenco”

When I first met Glenda Koeraus, the dancer who would later be known by flamenco audiences as Sol la Argentinita (and later known by me, only half-jokingly, as my guru)-- I was a basket case.

I’d already sobbed through the first half of a slush-filled winter. My marriage had recently fallen apart, my second book was failing to thrive. I was under-employed, broke, deeply lonely, and leaning on a cocktail of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications for an all-pervasive, unrelenting, weepy gloom I had begun to think might be permanent. Anxiety attacks had turned my spine into a fire-corridor of muscle spasms, and I had to wear black Velcro braces on both forearms, because

a galloping case of carpal tunnel was making me drop my coffee cup every morning and causing bright pain to shoot from my fingertips up to my neck every time I typed a vowel.

I ended up needing to get the kinks in my back ironed out often enough to befriend my massage therapist, fellow writer Sarah Falkner. In the middle of an esoteric conversation we were having between my grunts and moans, she mentioned that she had been taking flamenco classes.

I had always been very intrigued by flamenco. As a teen I had seen Carlos Saura’s flamenco adaptation of the movie Carmen, and it had made a deep impression on me. In the first shots, the fierce, indomitable-looking flamencitas of the dance company are stomping in unison across an empty stage with no music but the 12-count beat, the compas, pounding from their feet. Their brows are furrowed over dead-serious, black-lined eyes; the weightless grace of their ballet arms is offset by the bewitching, exotic swirls of their wrists and fingers, falling like leaves, rising like birds, stealing some treasure from the air, stashing it away with a defiant swing of their skirts. These women looked dark, fascinating, beautifully skillful and dangerous - so unbelievably badass, I felt impressed in the kind of way that young boys must have, when they first saw Bruce Lee movies.

I had muddled through a lot of classes in my life, but I'd given up after deciding I was incurably talentless. I had been serially humiliated by ballet instructors for never remembering combinations or developing sufficient turn-out; a famous modern choreographer, in a large summer class, once screamed, "Why are you making those faces? They're so weird!" I found I was slightly better at Afro-Haitian dancing, and took classes for a while, but, as a marshmallow -white, bleach-blonde Goth chick, I always felt like I looked a little ridiculous doing it. So I gave up dancing entirely and joined a gym.

But I jumped to invite myself to Sarah's flamenco class. I figured that even if I was hopeless, I could still wear a long swirl-skirt, battered legwarmers, and the fantastic shoes: character-ballroom-type pumps with clusters of actual nails pounded, like punk-rock taps, into the toes and heels.

The class was held on the warped, slanted floor of a squalid basement apartment in Park Slope -- the tenant of which was picking up extra cash by renting her living-room as a part-time “dance studio” (this transformation of space achieved via four cardboard-backed drugstore mirrors staple-gunned to the wall.)

It was low, poorly-lit, and cramped -- approximately eleven ungraceful middle-aged Brooklyn women were tripping over each other in bad hippy skirts. It was a scene I'd ordinarily throw money at and flee in under ten minutes. But the teacher, Sol - an Argentinian émigré no more than 23 at the time - was blazing from within with more sunshine than I had seen in months; a gorgeous spitfire of a young Rita Hayworth, hollering at the Brooklyn women in Spanish with the confidence of a four-star general, and attacking the space around her with a furious, capricious energy that turned on a dime from seductive to dismissive, raunchy to elegant, caressing to murderous.

The first time I saw myself stomping and scowling in one of those cheap mirrors, I felt something I had never felt before, in any other dance style. I felt that in the context of flamenco, as foreign as it was, and as weird as I am...I made sense.

As Sol once phrased it, "Once you get the fever... that’s it. You are hooked."

I was hooked. Flamenco grabbed me by the neck and enslaved me to the kind of hapless devotion you usually only see in drug addicts, surfers or religious fanatics. I was henceforth doomed to wander through New York's most depraved flamenco zones - to be yelled at in Spanish in firetrap dance schools in condemned buildings with cantaloupe-size dust-monsters, paint peeling in footlong curls from the ceiling, and mirrors warped unto funhouse convexity. I have endured the heartbreak of attending workshops where the instructor, a visiting artist from Spain, never bothered to show up. I have spent agonizing months never quite getting that step down, broken numerous wooden fans, and watched in horror as both of my pinky toenails fell completely off (they did grew back). I am now well into my seventh year of following Sol around like a junkie/disciple...and there is no turning back.

When flamenco first came to the United States, some 170 years ago, it was hailed in a newspaper report as being a treatment for arthritis, typhoid fever and (most interestingly, to me)… suicidal depression.

Flamenco music - the virtuosic, classical guitar letras , the contrapuntal clapping (palmas), the mournful, melismatic wailing - was first recorded in Andalucia in the mid-19th century. It is the music that arose out of the cosmopolitan melting pot that was the Iberian peninsula, which was ruled for nearly 800 years by a Muslim Caliphate of religiously tolerant Moors.

Numerous cultures enjoyed a free and open exchange in the Al-Anadalus province (until 1492, when King Ferdinand II forced everyone in Spain to convert to Catholicism), and these wildly diverse influences can all be heard in the distilled forms of the palos -- the rhythmic structures, modes and chord progressions that comprise over fifty styles of flamenco -- combining the contrapuntal rhythms of North Africa, melismatic wails evocative of both the Muslim call to prayer and lamenting songs of Sephardic Jews, rattles contributed by Byzantines, Gregorian influences from the liturgical Mozarabic chants left over from the Christian ceremonies of the Visigoths. The romantic Castilians put their own spin on it, as did the Romani, the nomadic gypsies who had made their way to Spain from ancient India. Flamenco forms survived in the gitanerias - the gypsy slums, where they were handed down through family clans for centuries.

Cut to: present day lower Manhattan. Two or three times a week, a very loose-knit, endlessly fluctuating and highly diverse group of women have been taking classes with Sol, on and off for years. As we slowly became more badass in our flamenco skills, I began to think of the regulars as my non-vehicular motorcycle gang, and dubbed them Las Malditas (“The Accursed” or “The Bitches,” depending on who you ask) -- a nickname which, I am proud to say, has stuck.

There is no average age or cultural background for the Malditas. Several are robust attractive girls in their late twenties and early thirties, there are occasional teenagers, a few of us are just north of forty. Nancy Villareal, an executive educational administrator from Peru, is 61 - and she has occasionally brings her 79-year-old mother. A male dancer may drop in occasionally, but it is usually all chicks -- quite a few gorgeous South American girls, a few nice Jewish girls from Long Island. A quiet but determined Frenchwoman, and a Dominican burlesque dancer show up on a sporadic basis. A tall, shy, non-English speaking Japanese woman always shows up for classes that involve fans. Our Korean filmmaker recently moved to France, but Lourdes, a gravelly-voiced Spanish former ballerina, seems to be around more than usual. I recently brought Gargi Shinde, my assistant, when she told me she had man-troubles. This turned out to be a thrill for the Malditas: the Kathak dancing Gargi had been taught in India gave her the perfect liquid wrists and hypnotic fingers for flamenco.

The Technicolor range of feelings in flamenco can be deeply cathartic, even if you're pretty repressed. It’s a place to enjoy being a girl in pretty ways you'd be too shy to embody in real life - and it also requires the unleashing of the feminine dragon in a way that I like to call “PMS times 1000.”

(Gargi, texted me the same night, after class: the charge she got from flamenco inspired her to boldly break things off with the guy she had been dating. She was exultant.)

I definitely saw positive physical effects, soon after I began taking regular classes. My carpal tunnel completely evaporated - I believe this is because the gestures of flamenco are, essentially, super-charged versions of the nerve stretches prescribed by my physical therapist - keeping my chest forward, shoulders and elbows back, rotating the wrists, isolating the fingers.

Flamenco is a pretty good overall tone-up, like any cardio regimen, but if you’re mainly looking to work out your ‘accessory muscles,’ it will probably hold no magic for you, nor you for it. Flamenco is an art form, and requires more dimensions of engagement than simple exercise.

What became really interesting to me, after a while, were the subtle psychological effects that flamenco was having on myself and other Malditas.

After a number of classes, I saw these women (and myself) slowly become more aggressive, grounded, and self-possessed. The biggest changes were in the way we began to carry ourselves, both internally and externally. Your posture changes - you start walking with your heart forward and your shoulders back in class, and eventually, you start walking that way everywhere else, as well.

“Flamenco is about expressing all of your feelings,” Sol explains. “Any feeling you can have, there is a flamenco song for it. You don’t have to understand Spanish."

Flamenco is too complex and has too much history to adequately discuss in one article, but suffice to say, the palos of flamenco, are somewhat like blues forms.

Heavier palos, like siguiriyas, are songs that come from the essential "black sorrow" of flamenco -- the pena negra, which the lyrics of a particular siguiriya gitana are often invoked to describe: " Pains without possible consolation, wounds that will never close, crimes without human redemption..."

Other dances -- lighter forms like the guajira or the bulerias, can be fun, playful, sometimes flirty. In a recent workshop, Sol's choreography required us to flip a fan open behind our heads, to frame our come-hither faces like a sun-hat. Then, seconds later, we had to be brazenly raunchy, whip open our fans and stagger around fanning our crotches like they were on fire.

Suffice to say: after enough of the old Andalucían voodoo, Pilates starts to seem too inane and textureless to suffer through; it’s like comparing a bag of chicken nuggets to sex with someone you love.

Anyway, getting fit is hardly the point of flamenco - it’s not about camouflaging your imperfections, but becoming rudely and defiantly beautiful and physically confident regardless of your age or shape, or whatever idiotic, ever-fluctuating metrics our consumer society uses to define ‘beauty’ this year. Most women end up carrying an unspoken apology for themselves in their bodies -- but after hanging around a flamenco studio, you learn that you are perceived as being more beautiful not when you finally starve yourself to death and have enough corsets and masks on -- but when you start revealing, as opposed to hiding, yourself.

“You work with just whatever you've got on hand,” Sarah explains. “Each of us

is making the most of the fat ass or skinny legs our mamas gave us. If we can't move our feet fast enough we rely on our matured emotionalism to carry the moment like the best French actress. The faces we make, contorted by extreme emotions of every flavor, are truly home-porn worthy."

While flamenco may be sexually empowering, it isn't explicitly sexy (unlike, say, belly-dancing). Sex with someone else isn’t the goal. It’s an autonomous sex that doesn’t require anyone else’s permission, approval or participation -- the dancer herself is brazenly enjoying her own sexuality. Even toothless gypsy women in their nineties do it, and there’s not a damn thing anyone can do but salute.

Unlike in American society, where the stock value of women is perceived as plummeting the minute they betray any signs of age or inflexible character, flamenco is a community in which women, regardless of age or body type, are cherished for their experience and accumulative ability to channel their emotions and transform them into the lightening flashes of dynamic aura-blast that is prized as great soul, or duende, in flamenco performers.

You can’t buy duende -- your soul has to be turned on to its highest wattage. There’s no way to fake it -- you just have to keep dancing and availing yourself to the weird mystery of it, and hope it hits you someday.

Flamenco stars are nearly the antithesis of the comely hotties of pop music fame. My favorite singer, Ginesa Ortega, has a voice that sounds like a emphesymic bassoon full of moonshine and bullet-casings. One of New York's most respected flamenco dancers happens to be an Asian woman, trained in Seville, whose body is shaped not unlike that of a Sumo wrestler. The renowned dance troupe Noche Flamenca’s star dancer, Soledad Barrio (the guru of my guru, Sol), is beloved by the critics at the New Yorker, but they don’t spare her vanity: “Experiencing the searing severity of Soledad Barrio up close could frighten a child,” they wrote, in their dance listings for April, 2009 -- adding, “Few adults come away unmoved.”

I actually believe that when women release themselves, and give themselves permission to be and feel everything they are -- monstrous, large, loud, brazen, occasionally ugly - they paradoxically start to age backward and become more comfortable in their skin. Maybe the expanded range of emotions in flamenco highlights, for us when and how we are beautiful; maybe it is learning to slam your foot down during a bulerias with a force of will that says fuck or fight that paradoxically informs you how, during an alegrias, to be more open, joyful and gentle.

Anyway, this expanded emotional vocabulary has an uncanny way of finding itself into the rest of your life.

Sarah Falkner wrote to me, via email: “Even if raised to be timid, if you stomp out enough golpes in the privacy and safety of the classroom, you eventually will feel quite natural putting your foot down with force in other situations, too. And when you swing your hips for the first time in a Tangos, I bet you ain't never felt that womanly before.”

“Many girls really need to break out of themselves. Students start as shy -- but flamenco grounds you," said Mariliana Arvelo, a Venezuelan flamenco dancer and instructor. "It gives you the tools to get everything out.”

Flamenco has always been the music of displaced persons and diaspora, but it also seems to be a particularly potent inoculation against Western-style female neuroses.

The scarier feminine emotions that tend, in our society, to be masked, repressed pathologized and/or medicated (e.g. grief, craziness, defiance, anger, brazen sexuality, desperation) are assets put to elegant use in flamenco.

"Flamenco is a union with your interior," Sol told me. "You may find things in yourself that you don’t like, but all those feelings are real. They happen. You can’t deny it, it’s not healthy. What better way to express it than dancing and stomping? Stamping into the earth - the power comes back to you!”

I realized, after taking classes for a couple of years, that many of my back issues were due to the fact that I had been carrying my body in a way that suggested that I had been stabbed in the heart -- I wasn't aware that my shoulders, my posture, all of my musculature had been contracting protectively around this emotional wound. I realized that I was carrying around an enormous amount of unprocessed grief - mostly because I really didn't know how to express it.

I realized I probably wasn't alone in having such unanticipated psychological breakthroughs, in flamenco -- so I started buying drinks for Malditas after class so I could grill them. To my great surprise, pretty much every Maldita I talked to was consciously using flamenco as a form of therapy.

A Maldita I'll call Maggie, a tall, soft-spoken girl who comes straight to class from her office, would confess no psychological discomfort whatsoever until her third glass of wine, during which she unleashed a long, profane blue-streak of corporate rage against an idiotic boss who had been torturing her in various ways.

“Flamenco enables me to express my rage without alcohol," she said, finally. "If I ever start snapping at my husband, now, he always asks me, 'Don't you have a dance class today?'"

“I call flamenco my brain shampoo,” said Sally Lesser, a costume designer (who you would never guess is 62. )

Sally and her mother had enjoyed going to flamenco performances together. Before her mother died, Sally would occasionally perform flamenco for her at her nursing home.

“My mother had Alzheimer’s, and she literally couldn’t remember who I was...but up to the very end, she always remembered how to do the palmas (clapping to the beat) for the compas.”

Another Maldita, who chose to be anonymous, lost her mother to an aneurism when she was six; her father abruptly remarried within a year. For her, flamenco is a place to process her rage at what she described as a childhood marred by an "archetypal evil stepmother."

What surprised me the most was when I finally, during interviews for this article, learned more about Sol's personal history. "I needed flamenco because I had so much trauma," said Sol. “When I first came to the United States I didn’t know anybody. I was 20. My sister had just died."

Back in Argentina, Sol's sister was hit by a car near her house. "Somebody shouted for me to come to the corner, and there I saw my sister, in pieces."

A big part of what saved Sol was the inspiration she felt watching Soledad Barrio of Noche Flamenca.

She now occasionally dances with the company - her "biggest dream come true."

“The fact that you do flamenco all by yourself, with no partner, made me feel like it was OK to be alone and in pain,” said Maldita Liza Frantzen.

A rather extreme example of this is the story of the dancer Andrea del Conte, whose sudden death sent shockwaves through the flamenco community in 2009. "We had a student performance that day, and she didn’t show up - that's how I found out," said Sol. "Nobody knew she had cancer. She was working up to the last second."

I firmly believe that if Anne Sexton, Virginia Woolfe and Sylvia Plath had taken flamenco classes, they’d have lived to write much raunchier, happier stuff in their old age. I hope to...but I didn't always. I think you discover something adamantine and indestructible in yourself by learning how to dance through long and uncertain bouts of emotional survival.

“It is true for all of the arts, but to dance flamenco well, you have to suffer. You can see girls in class who haven’t really suffered in their lives, and their dancing has nothing to say. The older that you get, the better you are as a dancer," says

Mariliana Arvelo.

When Mariliana was the substitute teacher for Sol’s class, this past summer, I never suspected that she had just lost her father.

“In the spring, I went back to Venezuela, because my father was very sick. On my first day back, I was crazy -- but I had bought this beautiful white fabric, because I felt like I needed to have this flamenco dress made. The dressmaker and I talked and cried together about my father.”

While her dress was being made, her father passed away.

“I picked up the dress on my last day in Venezuela. Now it is hanging in my room. I keep staring at it. I know I am going to make a dance for that dress. It has everything about that moment: my father, all my grief. It is like the dress is for a wedding I am going to have with my future-self."

Sarah describes flamenco dance as her "combo spiritual practice, martial art, medicine and Gestalt therapy.” I think that pretty much nails it. Flamenco is both exercise and exorcism. It converts trauma into art.

Flamenco has enriched me with a confidence and integrity that has made it impossible for me to be anyone’s doormat, and given me much more fearlessness about flying solo. I've been able to stand up for myself in personal situations that previously would have destroyed me. I've relied on classes to give me the strength to extricate myself from unsalvageable situations, process my grief, and to provide an outlet for scary aspects of myself I had been too terrified to confront, let alone accept. Flamenco helped me realize that even these parts of me can be integrated and transformed into beauty, power, and energy beyond aggression.

I have been able to use flamenco as a lever to pry myself out of a state we culturally define as mental illness -- serious depression -- and to arrive at a place that I tentatively describe as something like ...sanity.

During romantic doldrums, I’ve even found flamenco to be a fairly decent neurochemical substitute for sex.

One of the hardest things to learn, in flamenco, is how to remain conscious of everything your body is doing at the same time. Your arms need to be fully engaged, your elbows usually need to be further up or further back, your hands are "chewing the air" (as Sol once described in her fabulous broken English), your head needs to snap with the right attitude, you need to swing your skirt around and tuck your hips under and thrust your ribcage out and squeeze your shoulderblades together and count to twelve over and over so your feet can do a complex pattern against the compas, you need to listen to the guitarist, who might be drunk or stoned or speeding up or slowing down. And every once in a while, in the midst of all this, you find yourself actually emoting. These are the moments when I lose myself and am simply, totally absorbed in flamenco, and no matter what else is going on in my life, I feel blessed to be an accursed Maldita.

But Flamenco, Sol is quick to point out, is far from being all about the processing of suffering.

“Flamenco has so much open space for your personality. It’s not about the steps, it’s how you do them. It’s about doing it with an open heart, to express, to play. We all feel sorrow, desperation, exclusion. But flamenco is also happiness, celebration! It’s fresh air! Alegrias is about the beach and the sun, dresses and beautiful women. Bulerias are about making fun of yourself.”

I have no lofty plans for my flamenco dancing - it’s just the secret passion that makes me want to wake up in the morning.

I went to one of Sol's gigs the other night at a Spanish restaurant -- I wanted to see her first number, take some notes. Sally and Lourdes, two of the other Malditas, showed up, and we ended up hanging out and drinking wine.

When Sol surprised me about an hour later by suggesting I get up and do a bulerias, I was aghast . “Noooo!” I shrieked. “I am too drunk!” After botching a few ballet recitals in high school, I’ve been scared to death of dancing in public.

“That’s perfect,” she said. “Sooner or later, you’re just going to have to jump in and do it.”

I had my shoes with me, so I felt thumb-screwed by destiny.

A few minutes later, I summoned all my courage, made a very promising entrance onstage, full of fire and music…and then my mind went totally blank, and I forgot every step I’d ever learned. So I made a very hasty and somewhat unintentionally comical exit.

When I skulked back to the table, Lourdes was stomping and twirling her hands in front of her chest to remind me of the gesture I failed to perform “You didn’t CLOSE!” she shouted.

“I know, I know,” I said, embarrassed.

I usually joke around with Sol’s boyfriend/accompanist, the brilliant guitarist Christian Puig, who has the craggy, mournful face of an Argentinean pirate (when I anointed him an official Maldito, he gamely named himself “El Bastardo”). But after my aborted buleria, he couldn’t look me in the eye.

“I know!” I hollered. “Don’t say anything! I know you always tell the truth.”

He shrugged. “I always tell the truth.”

“That was like surgery,” I realized. “It wasn’t going to be pretty, it just had to come out.”

It cost me the momentary respect of El Bastardo, but at least I did it: I danced spontaneously, in public. I sucked, my worst fears were realized. Still, it was a relative victory: even trying would have been unthinkable, for me, not long ago. Now, having walked through the initiatory fire, it’s a real goal - I hope to redeem myself with a properly absorbed, spontaneous public Bulerias, before I die. The Bulerias, after all, is a dance about laughing at yourself.

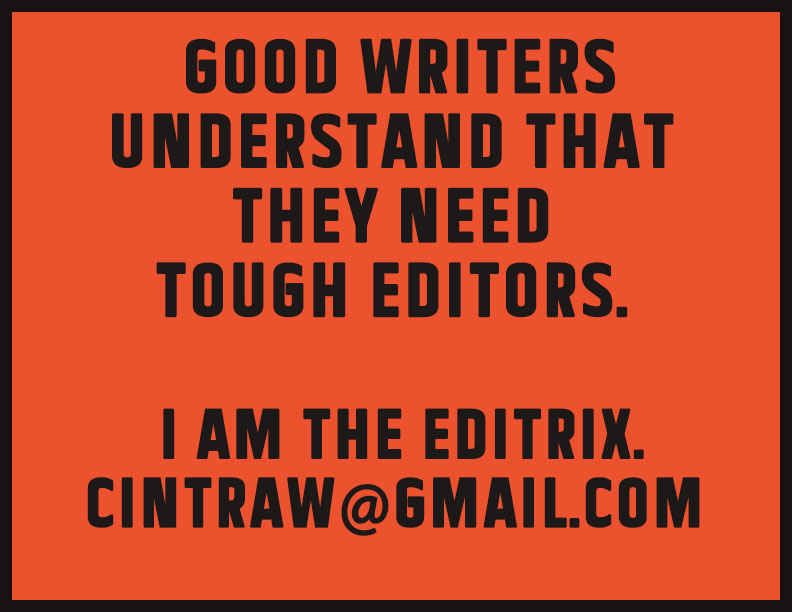

Artwork: “Muslim Spring,” oil on linen by Cintra Wilson, 2022